“The whole play is a female orgasm,” playwright Hannah Khalil reveals in a post-show Q&A.

Earlier that night, the first “line” in Khalil’s new play, “Hakawatis, Women of the Arabian Nights” is an enthusiastic moan, the beginning of an intimate night of storytelling.

“This isn’t the male orgasm that goes [draws fingers up to the peak of a mountain and back down],” Khalil elaborates. “This is a [motions fingers in hypnotic circles] orgasm.”

The first scene is deceiving. Hakawatis could easily fit the three act structure of, to use Khalil’s words, the male orgasm. A scorned king seeks revenge when discovering his wife’s infidelity (beginning) by marrying a succession of virgin girls night after night (middle) before murdering them after consummating the marriage (ending). A quick payoff.

Instead, the opening scene becomes the frame story for the tales to come. When a young girl named Scheherazade is married to the enraged king, she disrupts these gruesome nightly rituals by telling the king a story and then promising another if she’s saved. It’s a story within a story.

The next night, Scheherazade tells another story which finishes precisely where the next night’s story will begin. The stories interlock, like rings in a chain, weaving in and out of each other. Zooming out to the first frame, these stories promise Scheherazade’s safety…at least for that night. But who is writing these stories?

If this story sounds familiar, it is because the play’s source material is “Arabian Nights” or “1,001 Nights.” Though, Khalil has flipped the script. Here, the king is offstage and infrequently invoked.

Instead, the women of the Arabian Nights are centre-stage. The women craft stories that they sneak to Sheherezade from a sequestered room of stone and candles beneath the palace.

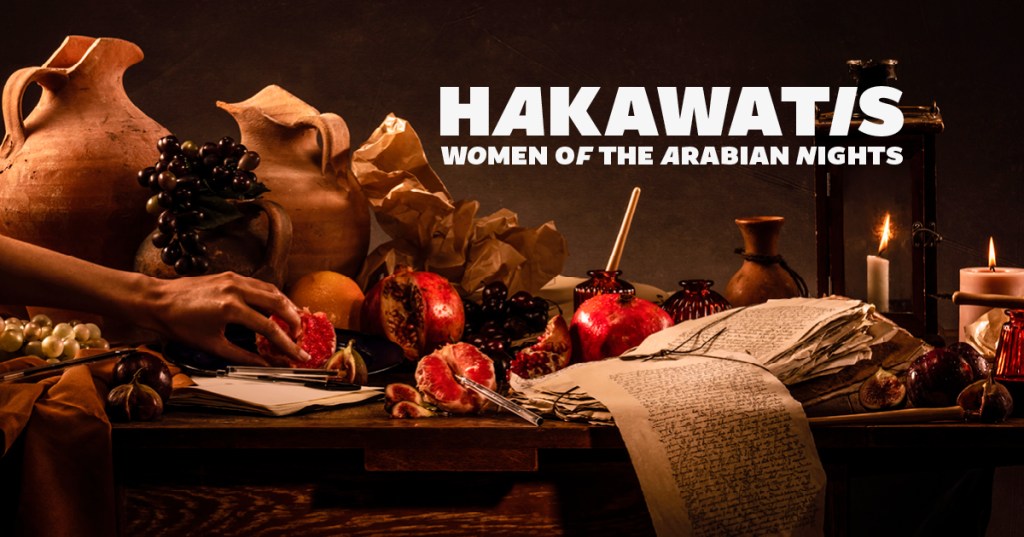

There is no story without a storyteller. This night, tucked into the candlelit Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe, 5 storytellers bring to life the ancient tradition of storytelling with the most innate tools—the voice, the body, and simple everyday items at hand.

The real success of “Hakawatis” is the chemistry between these 5 women. As the women develop stories they banter and they disagree, they encourage and they fall into very human emotional traps. This interplay creates a dynamic collection of contradicting and complementary stories sculpted by women as unique as the tales they tell.

“The first story, the one about the fisherman and the ‘gin’ [genie]—is entirely improvised,” reveals Khalil in the post-show Q&A. “It says in the script, ‘to be made different each night.’”

This is the moment the play sparks to life, when the flame is lit.

While the remainder is scripted, this improvised entry into the world of the hakawatis (meaning “storytellers”), draws me in and has me waiting with baited breath to witness a world painted for the first time from nascent words breathing their first exhale.

This breathing is underpinned by the show’s rhythms. With drumming and sliding violin riffs, onstage musicians create an atmosphere to suspend disbelief. The musicians set an audible heartbeat to each story that quickens and retreats, guiding the audience to believe their ears.

Director Pooja Ghai conducts a rhythm of her own. Ghai expertly builds tension in each scene, easing in slowly before quickening pace and bouncing between storytellers. At times there is chaos and confusion before arriving at a peak, lingering, and then releasing. In Ghai’s direction there is always a pay-off. Each story lands a punchline, crashes into a shocking reveal, or intrigues with an unexpected ending.

In “Hakawatis” Khalil and Ghai have crafted a play of nesting stories that warm and weave. In an age of feminist retelling of the Classics, with Madeline Miller’s Circe and Natalie Haye’s Pandora’s Jar, Hakawatis is refreshing in its approach. Stepping outside of the Western Classics, Khalil brings a female gaze to an Eastern relic, “Arabian Nights,” in a meaningful and satisfying reimagining.

“Hakawatis” is a candle that flickers, burning bright then waning. Its flame reaches upwards to an imagined escape before settling deep and stout on its wick. Its light is warm and delicate, yet potent and enduring. Like a moth to a flame, Khalil’s enchanting storytelling draws us in and smoulders.

All images are promotional photos by Ellie Kurttz (2022) and Shakespeare’s Globe.

Leave a comment