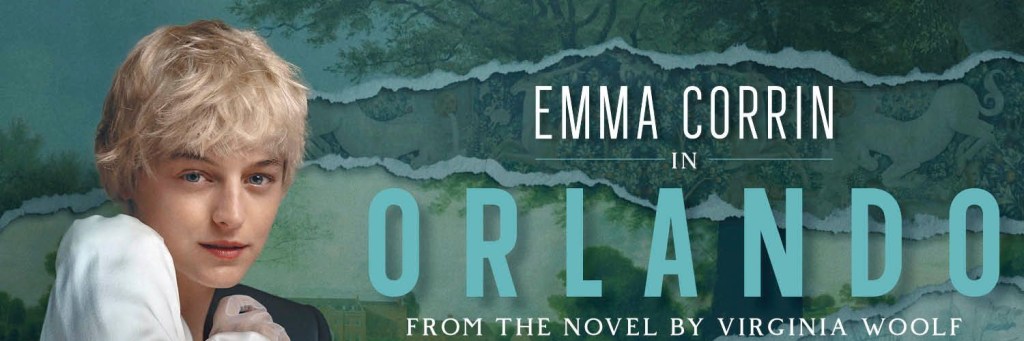

Emma Corrin is a paper doll. One costume peels off as another is pasted on. Before settling into an identity, it gives way to the next. Orlando, Corrin’s character in the eponymous play, lives a life that spans over 300 years, traverses land and sea, and fluidly navigates gender. Corrin, ever the shape-shifter, effortlessly plays the part.

Virginia Woolf’s late 1920s novel, Orlando: A Biography is often hailed as one of first trans novels. Translated to stage, Orlando is a bold choice that meets the moment. Orlando speaks to the present, while stripping back to reveal the deep roots of centuries-old conversations on gender, sexuality, and power. Emma Corrin, one of the most famous non-binary actors of the silver screen, easily embodies Orlando. It’s clearly a winning recipe, as evidenced by the 5-star reviews and excited audience reactions.

However, Neil Bartlett’s adaption is unbalanced. It leans too heavily into the present moment, adopting Twitter-speak at the expense of Woolf’s source text. Orlando becomes an elusive character that is neither self-assured nor self-doubting. Orlando and their world is difficult to pin down. It tries to be everything at once and misses the opportunity to say anything profound.

(The first half of this review has no spoilers. Read on for my criticism of the play’s ending and an Easter egg moment, if you don’t mind a spoiler or two.)

We are introduced to Orlando who, despite being born into wealth and land in the mid-1600s, rebukes society. When Elizabeth I comes to visit, we discover Orlando has begun a journey of sexual exploration and self discovery. Unsatisfied with the expectations of marriage and Elizabethan society, Orlando sets off on his own.

This is our first time jump. We follow Orlando to the Jacobean Frost Fair where he meets a Russian princess. The relationship burns bright and fast, but the flame goes out as quickly as it begins.

Fast forwarding again, Orlando chooses to leave this life behind and become an ambassador in Constantinople. Here, instead of dying, Orlando transitions into a woman.

And thats just the first third of the play. From there, Lady Orlando continues their journey of self discovery in equally as exotic scenarios but this time without male privilege.

This Orlando is nervously self-aware. The characters over-apologise in asides to the audience, leaning into internet talk about capitalism, colonialism, class, gender, and sex. While these moments speak to profound societal truths, they’re gone as quickly as a tweet. Instead of building intellectual momentum, the play lets off steam in short bursts that leave its final scenes hanging limp.

Although the characters on stage speak of Orlando’s bold self-assured character, this is not the Orlando I see onstage. This is an anxious Orlando that experiences flashes of confidence (mostly as a man).

It’s easy to look past this surface-level presentation.

Michael Grandage’s production is stylish and modular. The costumes rely on punchy symbols of eras — Elizabethan ruffles, Jacobean puffs, Victorian corsets, while maintaining modern silhouettes. The stage itself is also modular, with set pieces added and rolled away to evoke places and periods. Orlando’s visual world adapts but never transforms.

Michael Grandage’s Orlando is stylish without much substance. Its source material follows the moderniststyle of stream of consciousness, at the expense of plot. Instead, Bartlett and Grandage choose to emphasise plot at the expense of the deep intellectualism of Woolf’s writing.

On stage, Bartlett’s and Grandage create a fast-paced adventure that captures the feeling of Britain’s historical eras, but doesn’t say much. In the end, Corrin’s compelling chameleon acting is left painting with a dull, muted palette.

Audiences will undoubtedly find quotable lines that match their personal politics. From Lady Orlando’s delight in sex with women to takedowns of exploitative colonialism to calls to action in the class struggle. Neil Bartlett’s script creates many Gif-able moments.

Audiences will equally find Emma Corrin’s Orlando relatable and approachable.

If only the entire play were as strong as its quotable moments and its star.

(Spoilers start here)

In its opening scenes, the Virginia Woolfs (yes there are multiple Virginia Woolfs on stage) open the play with bold questions:

“Who am I?” “Who do I love?” “Do I have to follow the rules of society?”

But in its closing scenes, the play ends with limp Pinterest platitudes:

“I am here.” “I love wine.” “Choose courage.”

The ending is rushed and inconclusive.

After spending 90 minutes on Orlando’s character development, Orlando rushes into love thoughtlessly. The entire arc of Orlando’s search for love is unmoored from emotion.

But that just addresses the plot. Worse, the larger themes of Orlando fail to land.

It’s as if Bartlett couldn’t choose between two endings.

In one interpretation of the ending, love isn’t the rigid expectation of society. In this ending, women’s lives aren’t bound to who they marry and life’s purpose isn’t achieved with marriage. In this ending, Orlando offers an emancipatory definition of love

In another interpretation, Orlando, at this point in the 1920s, is told to wait another hundred years to find freedom. Presumably this ending points to the present moment, promising more freedom in 21st century feminism.

Both are compelling ideas. Unfortunately, neither idea is fully developed.

For your consideration, these are the last 4 lines of the play:

“Who am I?

I am Orlando.

What is my favourite time?

My favourite time is right now.”

The last line of the play could be a yogic mantra, speaking directly to the self-love generation of now.

Read another way, as Orlando walks into the sunlight and offstage, the last line could mean Orlando is walking 100 years forward into next adventures, or, in other words, into the present moment.

Unfortunately, this non-specific closing moment is unsatisfying.

“What is my favourite time?”

Personally, my favourite time was the beginning half of the play, but I am happy to hear Orlando likes it right now.

(As promised, the Easter egg)

It’s widely speculated that the thoroughly modern Virginia Woolf wrote “Orlando: A Biography” about her real-life female lover, fellow author, Vita Sackville-West. Look closely at illustrations of Orlando and you’ll find their form nearly identical to photographs of Vita. Many scholars have built careers analysing and assessing what Vita-as-Orlando can tell us about the struggling writer-artist and changing attitudes across centuries.

How does this translate to stage?

Virginia Woolf is onstage for nearly the entire show. Often, there is more than one Virginia Woolf onstage, writing the dialogue, directing the scene, and, in some cases, correcting Orlando’s behaviour.

In the denouement of the play, Orlando marries a sensible and boring Englishman. By the closing scene, the Englishman has faded from view and Orlando has retaken centre stage.

The husband returns onstage, this time dressed as Virginia Woolf. Orlando is pulled off the shelf from a bookcase of Virginia Woolfs.

In the final scene, Orlando speaks to their genuine love for their husband. Stepping towards Orlando, the husband-cum-Virginia kisses Orlando under the spotlight.

Indeed, wait 100 years, Orlando, and here you will find your public debut of your relationship with Virginia in London society. A love emancipated from societal expectations and as meaningful now as it was in 1928.

The moment lasts the blink of an eye, but carries 3 centuries of love, loss, and hope in a single kiss.

All images are promotional photos from Michael Grandage Productions and Marc Brenner.

Leave a comment